Hello friends, my name is Jack Raines, and I’m writing a guest piece for Tim this week. I also write a newsletter, Young Money, where I cover all things investing, finance, and careers. You can check it out here. Hope you guys enjoy today’s piece!

Hyper-specialization has been the name of the game in the 21st century labor force. The general consensus is that the best way to get ahead in life (or the job market) is a fanatical development of a specific skill.

Pick your niche, whether it be sales, or law, or medicine, or investing, or... you get the idea. Devote your time and effort to it, master it, and stand head-and-shoulders above others in your field.

Sure, it sounds good. But I have to disagree.

I believe that it is the hyper-generalist who has the competitive advantage, not the hyper-specialist.

1+1=3

The push for hyper-specialization relies on the fallacy of zero-sum skill development. Think about Mario Kart for a second. When you select your character and kart, you have to decide between different tradeoffs.

Luigi's kart has higher acceleration, but lower speed

Donkey Kong's kart has top speed and acceleration, but horrible traction

Mario has the most well-rounded kart, but it doesn't excel in any particular field

A strength in any given area is offset by a weakness in another area, meaning that the overall sum of skills are ~equal for any given kart.

What matters is which skills you choose to increase, and what tradeoffs you are willing to make.

We often view generalists and specialists in this same light:

Oh he's pretty good at a lot of things, but he's not particularly great at any one thing, aka Mario.

While he made sacrifices in some areas, he is dominant in _________, aka Luigi.

Mario Kart is a zero-sum game, but real life isn't. In real life, skill development is very much a positive sum game.

We aren't given 100 'skill points' at birth, that must be distributed across offsetting sliding scales. There is no limit to how many skills you can improve and master, and improvement in one field doesn't necessitate deterioration in another field.

In fact, skills build on each other. Honing multiple skills is actually a positive sum game, where 1+1 = 3.

Let's take writing as an example. Very few people are career "writers", but everyone can benefit from learning to write.

In June 2004, Jeff Bezos banned the use of PowerPoints in Amazon meetings and instead mandated that the organizers of all meetings create written memos to be shared before meetings begin. Check out this excerpt from his email to Amazon's employees below:

The reason writing a good 4-page memo is harder than 'writing' a 20 page powerpoint is because the narrative structure of a good memo forces better thought and better understanding of what's more important than what, and how things are related,” he writes, “Powerpoint-style presentations somehow give permission to gloss over ideas, flatten out any sense of relative importance, and ignore the interconnectedness of ideas.

Bezos' rationale was that in creating a concise, informative memo, the writer would be forced to fully think through their narrative.

What are the main points they want to convey? How can these points be defended? Where are the weaknesses and holes in their argument?

While PowerPoint presentations allow the presenter to gloss over information lapses, written memos immediately bring errors to light.

Everyone, from the CTO with an engineering background to the CFO focused on EBITDA and profit margins, benefited from stronger writing skills because they could better understand and share their thoughts.

The benefits of developing auxiliary skills doesn't end with writing. Learning other languages reshapes how you think and increases the number of people you can communicate with.

Studying psychology helps you understand the incentives and motivations behind others' actions, a soft skill that is useful in sales, investing, dating, and conflict negotiation.

Public speaking and dancing are two activities that will help anyone overcome anxiety and fear of embarrassment.

Skills aren't offsetting zero-sum activities, they are a positive sum game. Each additional skill increases the level of one's baseline existence.

Diminishing Returns of Specializing

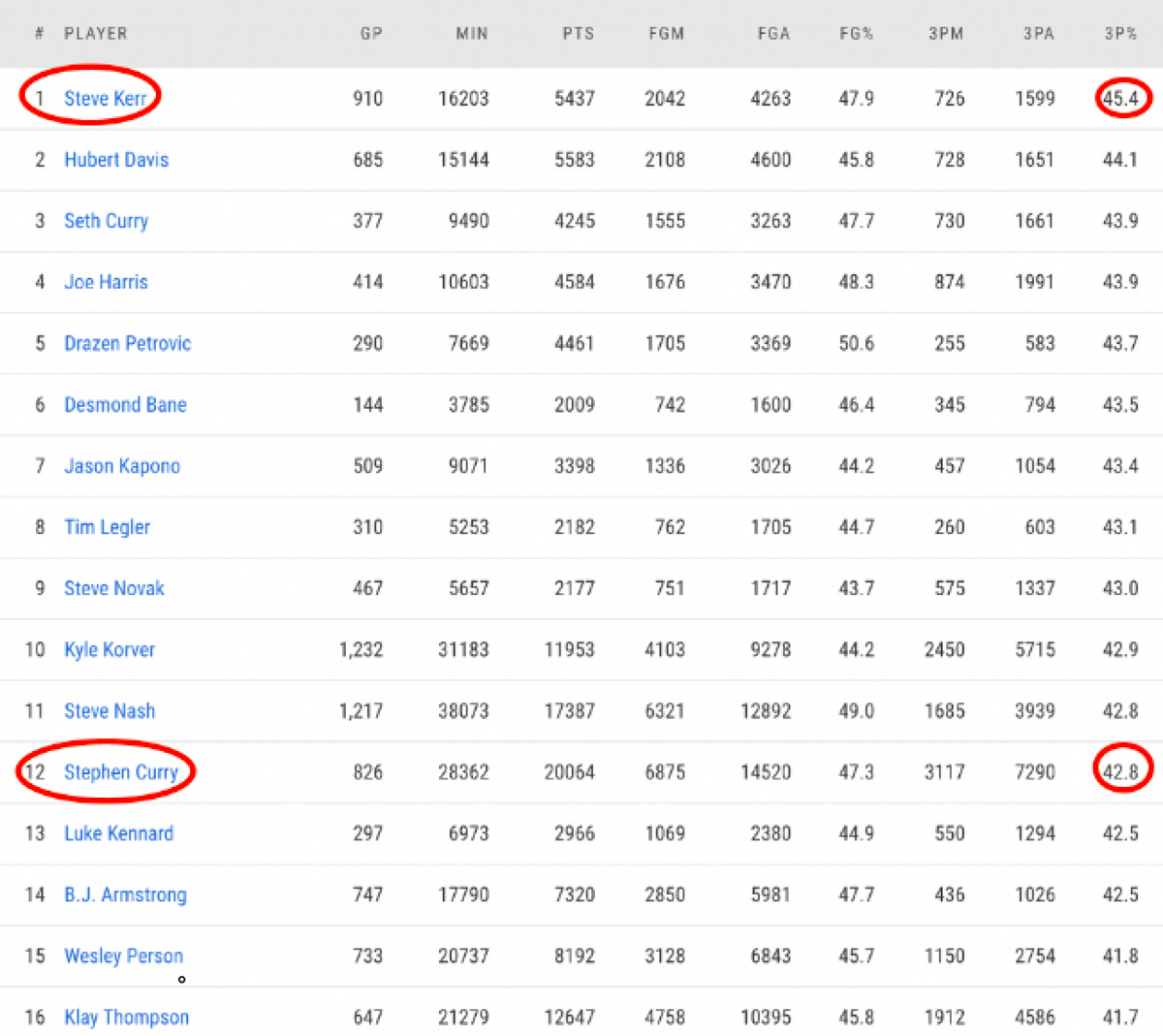

If I asked you who the greatest 3 point shooter in NBA history was, you would probably say Steph Curry. Yet statistically, it was actually his coach: Steve Kerr.

That's right, Kerr has the highest 3 point percentage in NBA history at 45.4%, vs. Curry's 42.8%.

Now if I asked you who was the better basketball player, the answer is obviously Curry. While Kerr was one-of-one from the 3 point line, that was it.

He rarely created his own shots, averaged less than two rebounds and assists per game, and largely relied on playmakers like Jordan and Pippen to set him up.

Kerr was the quintessential 3 point specialist: an important cog on a legendary team, but far from the best player on the court.

Steph Curry, on the other hand, is an artist on the court that can take over games. He is able to create his own shots, pull up from 30 feet, dish out assists all over the floor, and still snag 5 rebounds per game.

If you had to choose between building a team around a 30 year-old Kerr or 30 year-old Curry, you would choose the latter every time.

Statistically, Steph doesn't have the top 3 point percentage of all time, but no one will dispute that he is an elite shooter. It's important to differentiate between "mastering" a skill, and being the best ever.

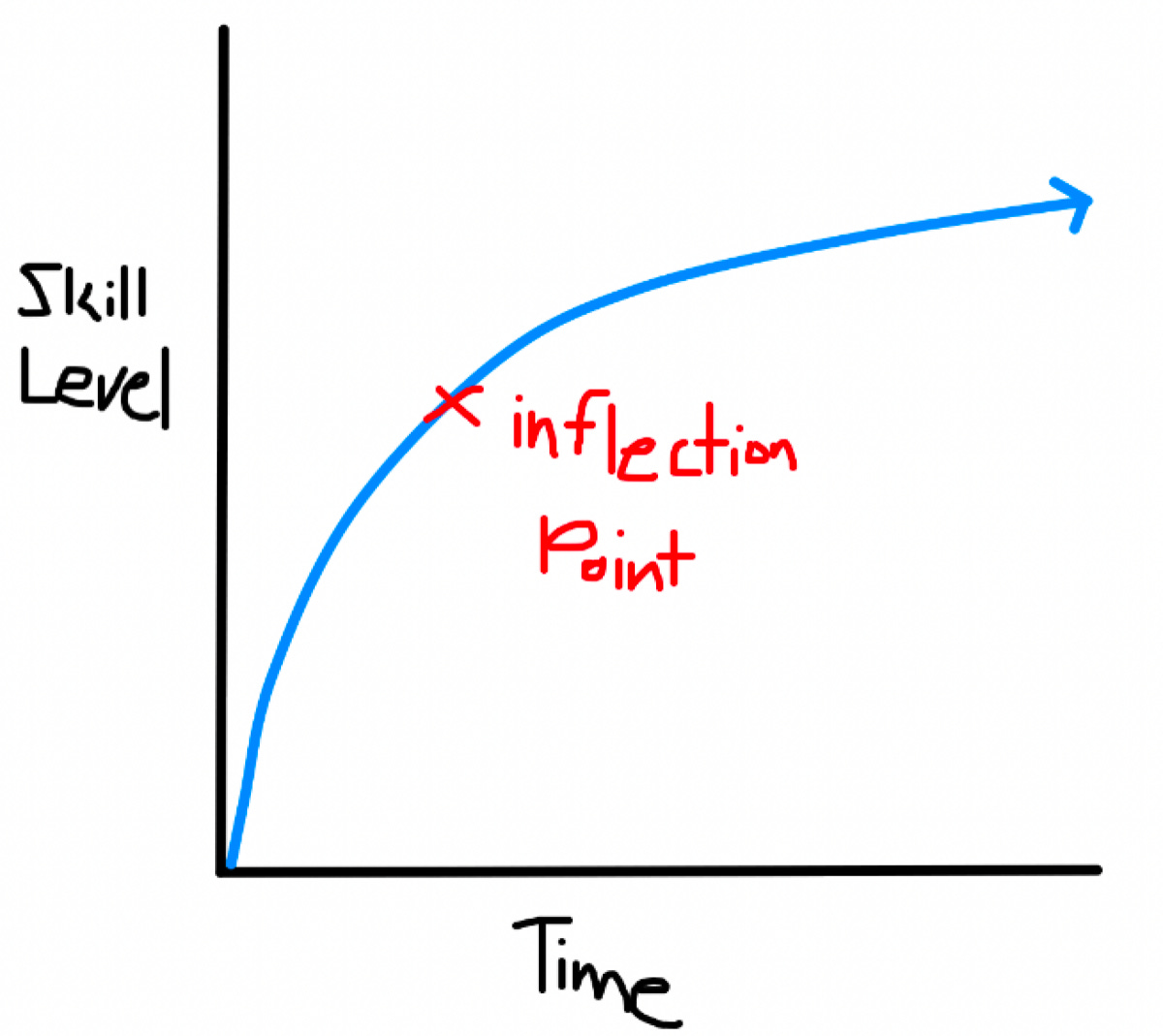

As your skill progresses, there are diminishing marginal returns on your efforts. The greats know when they are reaching this inflection point on return-on-effort, and redirect their efforts towards higher payout activities.

Tim Ferriss highlighted this concept of diminishing returns in a piece from 2007:

Generalists recognize that the 80/20 principle applies to skills: 20% of a language’s vocabulary will enable you to communicate and understand at least 80%, 20% of a dance like tango (lead and footwork) separates the novice from the pro, 20% of the moves in a sport account for 80% of the scoring, etc. Is this settling for mediocre?

Not at all. Generalists take the condensed study up to, but not beyond, the point of rapidly diminishing returns. There is perhaps a 5% comprehension difference between the focused generalist who studies Japanese systematically for 2 years vs. the specialist who studies Japanese for 10 with the lack of urgency typical of those who claim that something “takes a lifetime to learn.” Hogwash. Based on my experience and research, it is possible to become world-class in almost any skill within one year.

Any knife can cut, but the sharpest knife is only negligibly more effective than the next. A Swiss-Army knife, however, will come in handy in a variety of situations.

Diversifying your skillset doesn't make you less successful in your craft, it makes you more valuable.

Focus Is the Differentiator

Multi-talented is a competitive advantage, but multi-tasking is impossible. We are all, unfortunately, only granted 24 hours in a day.

You can become a prolific writer, learn multiple languages, get jacked in the gym, develop a financial acumen, and master a musical instrument in the same time period, but you can't work on all of these skills at the exact same time.

Just like you don't want to be specialist in life, you can't be a generalist in practice.

The key is targeted periods of hyper specialization across a variety of disciplines.

When it's time to write, write. When it's time to study, study. When it's time to lift, lift.

Your brain is like a web browser: If you have 100 tabs open at once, it becomes cluttered and hard to focus on any particular thing. If you are trying to write an article while Duolingo is pulled up in another tab, both your article and Spanish is going to suck.

Multi-tasking is a myth, segmented periods of hyper-focus is reality.

Limited Flexibility of the Specialist

The number one reason not to be a specialist? What happens if you no longer want to do what you specialize in? You spend eight years dedicating yourself to programming, and realize that you no longer want to code?

You have been working in finance for a decade, and decide that it's boring as hell? You've been doing the same thing day-in and day-out for years, and now you want to switch it up.

What happens if you just get bored?

You are going to find it difficult to escape the prison of your life's singular efforts.

In 1785, the English poet William Cowper once said, "Variety is the spice of life, that gives it all its flavor."

If variety is the spice of life, specialization must be the root of boredom.

Your career flexibility and the level of your life's excitement are directly related to your breadth of experiences, not the depth of any singular experience.

The most interesting experts in any field are those with divergent stories and passions.

Matthew McConaughey is a phenomenal actor. He is also a best-selling author and professor at UT Austin, who once wrestled a warrior in a west-African village.

Myron Rolle was an All-American safety for FSU who was drafted by the Tennessee Titans. Rolle is also a Rhodes Scholar who studied at Oxford University before graduating from FSU's medical school and matching to a neurosurgery residency at Harvard Medical School.

Tim Ferriss, who's 2007 piece largely inspired me to write this, is a best-selling author, company founder, investor, and world-class tango dancer, among other things.

Be a hyper-generalist in a world of hyper-specialists. A banker and a chef. A writer and a traveler. An investor and a linguist.

In a world driven by natural selection, the generalist is most prepared to adapt to his conditions. So be spontaneous, do some things that you aren't supposed to do, and have fun doing it.

If you liked today’s piece, check out Young Money here!

This instalment of Unfiltered is free for everyone. I send this email weekly. If you would also like to receive it, join the 50,000+ other smart people who absolutely love it today.

👉 If you enjoyed reading this post, feel free to share it with friends!

Hi, Jack via Tim. I've been a generalist all my life: amateur astronomer, ESL instructor and tutor, computer systems trainer, course curriculum and lesson writer, fiction and non-fiction editor, special needs student tutor, house cleaner, professional organizer. I keep learning new skills in each to keep my "value" high.

As a master of some myself, I loved this! Good stuff Jack!